INTRODUCTION

Come hither, wanderer. Before you lies the land of Barantine—the Grand Republic. You come not to a kingdom of simple lords and kings, but to a realm shaped by ambition, trade, and the dreams of free men. Barantine is a place where a traveller —yes, even you—can one day rise from the dust of the open plains to the polished marble of the Republic Senate.

But the road is long.

Here, the sun bakes the ochre cliffs and whispers through the dry savannas, carrying tales of centaurs in the trees and faeries singing by moonlit rivers. The wilderness stretches untamed and mysterious, speckled with forgotten ruins and shadowed by legends too old for history. Barantine’s lands are rich, its monsters prowl in the dark, and its past—haunted.

And yet, beyond the meadows and old temples lies civilisation: shining cities of stone and braziers where merchants barter fortunes, senators whisper conspiracies, and cohortes patrol with sharp eyes and sharper swords. Here, a man is not born into power, but earns it—or takes it.

You are no longer merely a traveller, are you? Will you climb from the wilds of the land and the gutters of the subura to stand among the patricians in Ryton’s forum? Will you uncover secrets buried beneath moss and myth?

The Republic awaits. And in it, so too does your story.

IN THE WILDS

Let us imagine you are a traveller from afar, and you have just landed on the coastline of Barantine. Not a port, but an empty beach, and without further pause to take in your immediate surroundings you hop off your boat, sling your explorers bag over your back and begin your adventure.

What would you be welcomed with? First of all, the dry heat and and a sky scant of clouds. A light blue sky, nearly white as the light from the sun warms you. Barantine’s winds cool you, creating a prefect equilibrium. The coasts and beaches are hilly hinterlands, with sandstone cliffs, wild grass and flowers, and the occasional grove of verdant trees to promise you shade. Beyond the coast, Barantine’s wilderness evens out into vast plains and savannas, occasionally touched with low rolling hills, valleys, gorges and small forests. Such biodiversity is more prevalent in the north and west of the land. To the far south especially, where it is hottest, it is an expansive, arid savanna, that breaks into a small sandy desert that trims the southern coast. Very much like it’s climate, Barantine’s terrain is balanced with its abundance of rivers and streams that flow through the realm.

Now, after days of travelling off the beaten path, you eventually stumble upon a road that cuts through the long wild meadows and, following the road, you discover the land around you changes slightly. You see a milestone, and then another, and another, guiding you to the nearest settlement or shrine, the latter being visibly apparent as you find such effigies dedicated to Barantine’s official religion: The Green Faith – dotted close by the road.

They are stone altars or statues depicting something from The Green Book; be it a holy symbol, a prophet or a saint. Some look long abandoned and forgotten – nature already claiming the stone back to the earth as moss, grass or vines obscure the shrines and path toward it.

Now you are passing through land that has been touched by mortal hands. Verily do you find fields of grain, olive groves, vegetable patches and orchards rife with trees bearing plump fruits. Such tended lands often circulate the rural communities across Barantine. Some communities are a simple gaggle of stone, red roofed huts, whereas others show a grander presence. Aye, such tended land is permeated by great villas – sprawling estates that demonstrate the wealth of the owners. Out here in the countryside of Barantine, there are no ubiquity of taverns like in The Ivory Isles of parts of The Mainlands, though they do exist here and there in the rural villages. In the villa estates a traveller like yourself could find rest and refreshment, but certainly at a higher price and usually in a place that offers more comfort. In the villas there are farmer’s sleeping quarters, bathhouses, Graenician shrines and beautifully tended gardens.

But let us suppose you don’t have enough coin to purchase a night of warmth and food at a villa, or even enough to stay at a small village’s tavern, and you find yourself back on the road, and into the wilds.

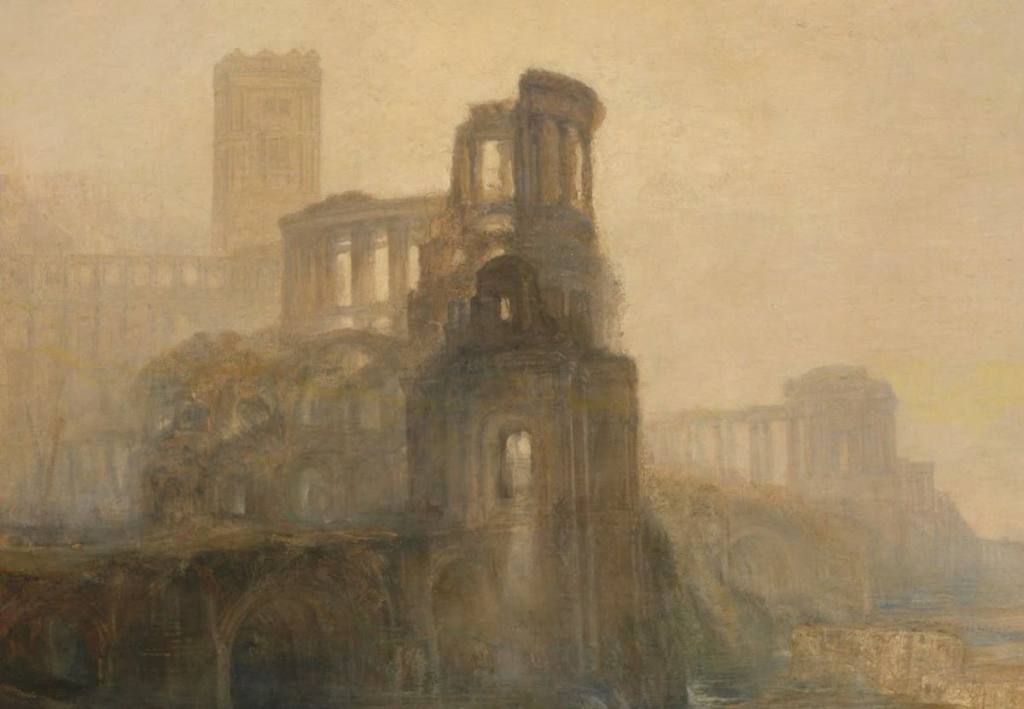

Well then, you would sometimes spot a strange structure in the distance. Upon a closer gander, ruins, forgotten by history can often be found off the trail in the wilds.

From the foundations of abandoned forts, to empty, strangely designed tombs and temples that house forbidden lore of Barantine’s dark past. Aye, much of Barantine’s history is a blur but from what is known, it had a dark, forlorn aeon – from it’s time as Laurica where God Kings and Devil people ruled, to it’s rise as a mighty continent-spanning Empire. Such ruins are rare to find by the road, so it could be by chance when you are trying to find some shade from the baking heat that you follow a gorge into a forest and find nestled in the verdant depths the mouth of a stone temple bearing eroded pictographs and indecipherable doggerel etched around the entrance.

And just because they are not touched by civilised people, that does not always mean they are empty…

Aye, another reason why such structures are left alone is because curious travellers such as yourself unwittingly enter into a lair of creatures that coexist in with man in Barantine.

A recent Barantini explorer by the name of Caesar Drusus is known to you as a prolific scholar who records the various creatures found across The Westlands, and certainly in Barantine. You have the typical creatures; goblin gangs, blemmyae mobs, the odd wandering ogre hunting for humans. But there are stranger things. From Lamia, cockatrice, gorgons and minotaurs, hiding in the depths of these structures. But not all monsters be so apparent. In your travels you have passed by isolated villages that are also nestled in the wilderness. And there they worship a warped version of the Green Faith, performing strange ceremonies and erecting obscene obelisks for supposed Graenician prophets, martyrs and saints that don’t even exist in The Green Book. Wary of such people who seem to be lost in a parallel time-scape, you quickly make your way back on the road, eventually realising that the baking heat of the sun might not be the worst thing out here.

Alas, all this sight of woe and terror should not deter you on the beautiful side of Barantine’s fauna. Oft do you sight the wondrous creatures – the shy but elegant centaurs for instance. When you spy upon them in the trees to watch them in small herds gallop across the fields, hunting game with their spears and bows, ahh, it is a marvellous sight to behold!

Sometimes, when you curl up against a tree upon a rainy night in a small forest by a waterway you hear the singing of faeries – of nymphs and pixies. Again, like with the sight of centaurs, to hear such music in the night gives you rest that there is always beauty to be found in Barantine – even in the most wild of places.

You have kept yourself by the waterways and well travelled roads of Barantine, making sure your waterskin can always be replenished and your belly full with a plucked fruit from a heavy hanging tree. You have crept through dark ruins, slept in simple taverns, or bathed in a wealthy nobleman’s bathhouse for a sum.

But now, it is time to leave the open wilds of Barantine, and step towards civilisation!

CIVILISATION

Now, among your travels in the wilderness of Barantine, you will have passed through some estates where you were privy to the access of the owner’s libraries, which is very common for Barantini nobles to have. And in that time, you had a good read and understood more about Barantine’s society.

Alright, so hark well. Barantine is a unified democratic Republic, and it prides itself as a united confederation of nations that focus on the acquisition of trade, making the Republic a trading powerhouse – its the wealthiest nation in The Westlands, and some even speculate it’s the richest, powerful nation in the known world! Barantine is not only the richest nation in The Westlands, but also the largest. It is known across the seas as “The Grand Republic” or simply “The Republic”.

Historically, the Republic has endeavoured to maintain a position of neutrality in conflicts across the Dark Earth, adhering steadfastly to its foundational identity as a trade alliance. This commitment to non-intervention has been largely consistent—save for a singular exception during the Second Crusade of the 9th Century. Under the leadership of Sovereign Chancellor Croton, the Republic departed from its neutral stance to lend support to the crusading forces, in a unified effort to liberate the lands from what was deemed Sothanic heresy. This greatly impacted trade between the FIS, which is a great source of imported income for The Republic.

The Republic: Social Structure, Governance, and Civic Life

Throughout history, the Republic has cultivated a reputation for diplomatic prudence and political sophistication, consistently striving to maintain peaceful relations with foreign powers. This deliberate neutrality has earned it enduring respect across the Westlands and beyond. Yet, peace should never be mistaken for passivity. Unlike the free cities of Pune, which often rely on mercenary forces, the Republic maintains a loyal, disciplined standing army. Its legions—hardened by rigorous training and steeped in centuries of military tradition—stand as a testament to the Republic’s enduring strength and strategic foresight.

Social Structure

Barantine’s society is defined by a tripartite class system, offering a degree of mobility uncommon in most nations across Dark Earth. At the apex stand the Patricians—aristocratic elites who hold substantial wealth, political influence, and control over key territories. Beneath them are the common citizens, comprising of labourers, craftsmen, merchants, and soldiers. These individuals form the backbone of the Republic and retain the right to ascend the social hierarchy through achievement in trade, politics, or military service.

The third class consists of Metics—foreigners and non-citizens residing within the Republic. As a metic yourself, you’d be required to obtain a metic pass from a designated forum within a city or major town. This pass legitimises one’s presence and grants the freedom to travel and conduct business within the Republic’s borders. Remarkably, metics may attain full citizenship by serving seven years in the Grand Army. Upon completion of their service, they are granted the full rights and privileges of a Republic citizen, including land ownership and voting rights.

Historically, the Republic also once recognized a fourth class—slaves. However, centuries ago, it was abolished following the discovery that free, compensated labour yielded greater productivity and societal stability than bondage ever could.

Governance

The Republic is governed as a representative democracy, overseen by a central Senate. Senators are appointed from among the Magistrates, who serve as governors and government officials of the Republic’s various regions. From this governing body, a Sovereign Chancellor is elected to serve as the executive head of state for a term of twelve years, with strict term limits in place to prevent tyranny and hereditary rule.

Each constituent state of the Republic maintains local democratic institutions. Assembly Halls—located in urban centres—host public votes to elect Tribunes and Magistrates. Tribunes serve as representatives of the people, wielding the authority to propose or veto legislation. Magistrates, meanwhile, are charged with upholding regional security and overseeing administrative governance. The highest offices within this structure include Governors—who represent their states at the Senate—and Consuls, who are elected by the Senate to oversee national governance, law enforcement, foreign policy, military command, and religious affairs.

The Senate convenes in Ryton, the Republic’s capital and largest metropolis, situated on the eastern coast. This city is the political heart of Barantine, home to ten million citizens and a symbolic centre of democratic power.

Social Mobility and Ambition

As a metic, your future lies unwritten. With a metic pass and sufficient determination, you may rise through the ranks—perhaps beginning as a soldier, then a citizen, and ultimately a respected patrician. The Republic uniquely rewards merit and ambition, offering a clear, if competitive, path to power.

However, this openness has bred its own perils. In a society where the ambitious may rise, so too will others seek to hold them back. Political intrigue, corruption, and clandestine power struggles are common. Assassinations, fraud, and scandal often lurk behind the marble columns and golden rhetoric of the Republic’s elite. Still, the Republic endures, and its economy continues to flourish—anchored by vast trade networks across the Westlands, the Mainlands, and Pune.

Family and Cultural Norms

Social norms in the Republic remain traditional in some respects. The average household is patriarchal, with men retaining legal and financial authority. Women, while barred from holding public office, do possess voting rights—granted only through lawful marriage.

Religiously, the Republic upholds The Green Faith as its official doctrine, a belief system founded by early zealots of The Creator and The Twelve. Over time, however, the Republic has become the most secular realm in the Westlands. While the Green Church still maintains influence and temples remain active centres for ceremonies and festivals, religious fervour has waned in many urban regions.

Freedom of religion is protected, provided no sect undermines public order or to usurp the Graenician belief. In the cosmopolitan cities and southern provinces, diverse beliefs are tolerated, even welcomed. In contrast, northern and rural regions remain deeply devoted to The Creator’s Twelve, and may exhibit intolerance toward followers of foreign faiths—such as Sothani or Santhiagans. Religions that call for human sacrifice are outlawed across the realm.

Despite this, many cities accommodate enclaves of various races and faiths, often with their own elected tribunes representing their interests. These districts serve as cultural sanctuaries but do not impose confinement— they are free to travel and reside throughout the Republic.

Demography

The population of Barantine is predominantly human. Owing to the nation’s vast and varied geography, regional differences in appearance are notable. In the northern provinces—such as Sortaly—inhabitants often possess fair complexions and lighter features, bearing a close resemblance to the people of the Ivory Isles. Across much of Barantine, the general population is characterized by bronzed, pale-toned skin, with a wide range of hair and eye colours typical of the human species.

In contrast, the southern regions—particularly areas like Rhodon—are home to individuals with olive to darker complexions. These populations frequently exhibit dark hair and eyes, bearing similarities to the people of northern Pune.

In addition to its human majority, Barantine is home to a minor but distinct population of gnomes. Many of these gnomes reside in the Understates, though small enclaves persist in the remote northern wilderness and settlements of Sortaly. Gnomes retain their characteristic features regardless of region: fair or ruddy skin, light hair hues, and pale eyes are consistently observed across their population.

What distinguishes Barantine gnomes from their counterparts elsewhere in Westland is their cultural assimilation. They commonly adopt the traditional attire of Barantini humans—togas, robes, and sandals—blending seamlessly with the broader aesthetic of the Republic. In adherence to ancient Imperial customs, male gnomes often shave their beards, a practice rooted in the belief that facial hair is emblematic of barbarians and duergar.

Gnomes in Barantine are notably zealous in their loyalty to the Republic, often described as among its most fervent patriots.

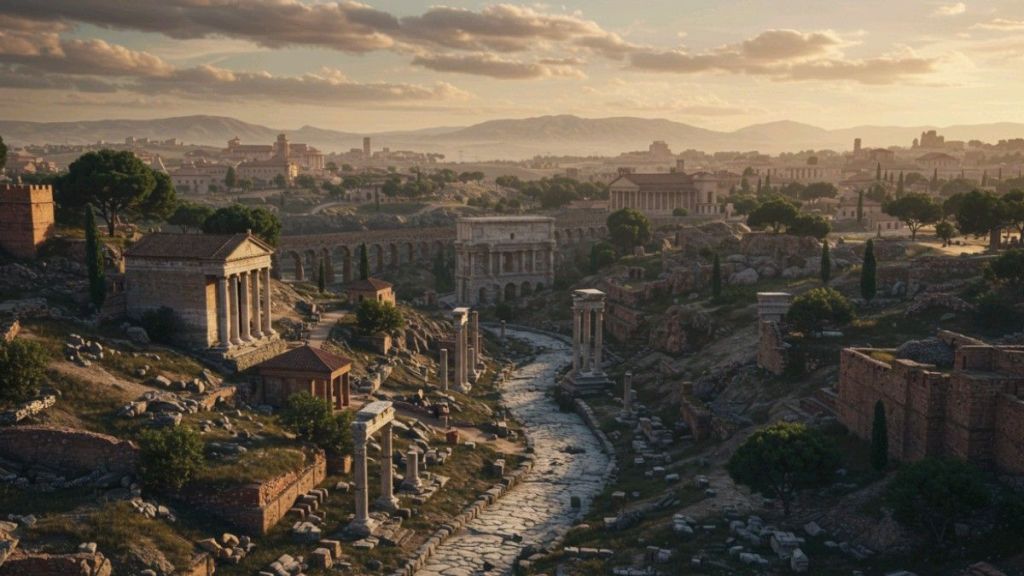

Toward the Cities

Much has been said of the Republic’s ideals and inner workings. But by Laramund! Now, it is time to leave the theoretical behind and step into the living world—into the bustling, breathtaking cities of Barantine.

SANDAHAR

Imagine yourself in the deep south of Barantine, within the province of Sanence, making your way toward Sandahar—the first city you’ve seen since setting foot in this arid, sun-drenched part of the land. As you travel, the roads become more defined, gradually converging into well-worn routes that feed into the city’s periphery. Scattered across the surrounding hills are clusters of sandstone dwellings with terracotta rooftops, interspersed with columned courtyards, orderly orchards, and small but productive farm plots. Caravans and convoys pass you by, moving steadily along the arterial roads leading toward the coast, where the city’s ancient walls rise in the distance.

From afar, it’s clear that Sandahar is no modest settlement. Though fortified by weathered stone, the city’s sheer scale is remarkable. The wind carries with it the ambient murmur of life—markets, temples, and a million voices blending into a low, resonant hum. Sandahar is the Republic’s second-largest city, home to over two million citizens, and known for its constant flow of goods and people from across the Republic and beyond.

As a foreigner—a metic—your presence in the Republic requires official sanction. Without a metic pass, your exploration of Sandahar would end swiftly, likely with an escort to the city dungeons and a passage back to the sea – usually, on the next boat leaving, regardless of where you whence came. Upon reaching the gates, you quickly identify yourself to the guards and declare your intent to register, not wanting to be seen as a trouble maker. With little ceremony and much indifference, they escort you across the city, past arched halls and bustling boulevards, to the Office of Foreign Affairs, located at the heart of Sandahar’s bustling port.

At the foreign office, you are questioned, catalogued, and assessed by a cadre of Republic officials. They record your origins, your physical features, your date of arrival and your declared intentions. Then you must pay a substantial one off fee – twelve gold crowns! Failure in providing this would also mean a one way trip to the ports and board a boat leaving the realm. But, luckily, you have that amount on you. Upon successful registration, you are granted a metic pass, along with a personal symbol that is tattooed onto your body at a location of your choosing. This mark, the same as a symbol etched on your documentation, grants you the right to reside and travel within Barantine unimpeded. Copies are written by scribes to ensure good record keeping. With a final nod and a faint smile from the clerk, you are now an officially recognized traveller—perhaps even a future citizen—of the Republic.

The Streets of Sandahar

The streets of Sandahar follow a strict grid layout, lined with stonework buildings and wide cobbled roads intersecting at calculated intervals. Drainage canals run openly along the roadsides, a testament to the Republic’s urban engineering, and aqueducts supply the city with fresh water from the hinterlands.

At the heart of the city lies the Forum of Sandahar, a grand district adorned with grandiose architecture and statues elevated atop a hill and reserved for aristocrats, government officials, and the wealthy elite. The architecture here is defined by sweeping arches, stately columns, and towering structures of concrete and marble. This is where libraries flourish, temples rise atop great podiums, and bathhouses and odeons serve both leisure and public discourse. The grandeur is unmistakable: market bazaars sprawl through wide avenues, perfumed noblewomen drift past fountains, and the air itself feels more refined. The forum is secured not by common guards like the ones you met at the gate, drab in leather armour over white tunics, but by Justiciars—elite peacekeepers clad in steel segmented armour and bearing the blue-plumed galea helms that mark their distinguished rank.

Beyond this stately core lie the residential quarters, where the city’s vast population resides. Most live in insulae—tightly packed, multi-storey tower blocks made of stone, complete with balconies and terracotta roofs. Though signs guide the streets, the sheer density of buildings and people often turns Sandahar into an urban labyrinth.

Among these districts, you find the common amenities of Republic life: amphitheatres, bathhouses, temples, and workshops. The amphitheatres, once venues of bloody gladiatorial combat, now serve a reformed purpose. Following the transition from Empire to Republic, mortal combat was abolished—though beasts and creatures from the wilds are still brought in to fight, often to the death against each other or other gladiators. Gladiators now train and spar against each other for sport rather than slaughter. For those craving bloodier entertainment, many cities across Pune remain the preferred destination.

The Subura: Life on the Margins

With your coin purse growing lighter, you find accommodations not in the comfort of the forum’s inns or popinae, but in the Subura—Sandahar’s sprawling lower district, often referred to as the slums. Here, the tower blocks rise higher and seem to be in need of repair – particularly at the upper levels. The streets are narrow, congested, and teeming with life at all hours. Overhead, washing lines criss-cross above the thoroughfares. Below, both vigiles and criminals roam, often indistinguishable at first glance. Vigiles are the city watch – like those who you met at the gates. As it happens, law and order is maintained by three cohorts. The vigiles usually guard the gates, patrol the subura and the city at night. The Urban Cohort is a legion dedicated to fighting more serious crimes and chaos, such as riots, crowd control and fighting gangs. The justiciars are the elite force tasked with carrying out the will and protection of the elite.

The Subura is where society’s edges blur: black markets thrive, illicit dealings fester, and brothels dominate street corners to serve all walks of life. Taverns bustle with travellers, bounty hunters, merchants, and the occasional clandestine patrician seeking indulgence far from the eyes of their peers.

At one such tavern, you secure a room. The establishment is worn but lively. The innkeeper offers you a room and introduces a tavern maid who leads you up a winding stairwell to a cramped chamber beneath the creaking eaves. She offers more than hospitality, unveiling her simple tunic to reveal her nakedness to you. She can be yours too —for a price. Whether you accept is a matter left to your discretion. I’ll..I’ll leave you two be to make your own decision.

A New Day in the Republic

It’s dawn in Sandahar, casting a grey light over the Subura. From your modest balcony, you watch vigiles apprehend a pair of street youths—likely pickpockets—dragging them off toward the dungeons beneath the guard towers. The Subura never truly sleeps. Drunken brawls erupt, revellers stumble through alleys, and madmen on opiates howl through the night. The city’s chaos makes you almost long for the quiet of Barantine’s wilds.

And so, the question of crime and punishment arises.

In Barantine, execution is outlawed—unusual in a world where death is common. Minor crimes result in fines or short imprisonments in the jail cells of guard towers, such as the two miscreants you see below. Serious offences lead to brutal punishments in the city dungeons: floggings, starvation, drowning and other tortures are meted out before offenders are released—who are then branded on the skin with their crimes for all the world to see. Repeat offenders, along with convicted rapists and murderers, are exiled to Pune, condemned to slavery or fodder for foreign warbands. This policy, championed by Sovereign Chancellor Croton, emerged from recent trade agreements with the Federation of Independent States (FIS), allowing the Republic to export its undesirables rather than execute them. Slavery may be outlawed in Barantine but many nations in Pune still find it a thriving industry. Before this, repeating offenders were punished for longer periods of time. Convicted rapists were castrated. Convicted murderers had their hands cut off.

The Tapestry of Cultures

As the city stirs, you explore further, discovering the migrant districts nestled within the Subura. For instance, here dwell the Sodian communities—horned folk who have transformed their quarter into a reflection of their homeland. Markets brim with strange meats and heavy metals, and fighting pits serve as both entertainment and tradition. Older generations reside in the insulae, while newcomers pitch tents in crowded squares, clinging to ancestral ways.

You pass through the Sothanic Enclave, where the faithful of a foreign god seek safety in numbers, and the Cathani District, home to well built, hairless, stone-skinned humanoids who industriously expand and fortify their quarter. These enclaves function with remarkable autonomy, often electing their own tribunes to represent their interests within the broader Republic. Though separate in appearance, they are not confined—they are free to live, trade, and travel as metics or citizens.

This accommodation is no accident. By giving newcomers a place to belong, the Republic preserves its harmony. Peace breeds productivity.

And what of your role, traveller?

In the tavern you’ve called home, bounty boards are cluttered with quests, whispers of gold and glory. Mercenaries murmur over maps. Adventurers prepare for departure. Somewhere in Barantine, your path awaits.

Time to find out.